In White v. Wear (2022) 76 Cal.App.5th 24, the California Court of Appeal upheld an elder abuse restraining order that stopped a stepdaughter from making or facilitating any changes to the estate plan of her 94-year-old stepfather — a man whose multi-million-dollar trust had already been secretly amended to disinherit his biological children. That case illustrates a reality that many families discover too late: when someone uses undue influence or financial exploitation to change an elder’s trust or will, you are not facing a single legal problem. You are facing two. And filing both a financial elder abuse claim and a trust contest together creates litigation leverage that neither claim offers on its own. Here is how the two claims intersect under California law, why filing them together matters, and what the process looks like in practice.

What Financial Elder Abuse Means Under California Law

California defines financial elder abuse broadly. Under Welfare & Institutions Code §15610.30, financial abuse occurs when any person takes, secretes, appropriates, obtains, or retains the real or personal property of an elder or dependent adult for a wrongful use or with intent to defraud. The statute also covers anyone who assists in these acts and anyone who accomplishes them through undue influence as defined in §15610.70.

An “elder” under California law is any resident aged 65 or older. A “dependent adult” is a person between 18 and 64 with physical or mental limitations that restrict their ability to carry out normal activities or protect their rights.

What makes this definition so powerful for litigation is the breadth of what counts as “property.” The Court of Appeal in Bounds v. Superior Court (2014) 229 Cal.App.4th 468 established that financial elder abuse encompasses the right “to dispose of the property by sale or gift.” This means that when someone uses undue influence to change an elder’s trust — depriving the intended beneficiaries of their inheritance — they are taking a “property right” from the elder. The elder’s right to have their actual wishes carried out is itself the property being stolen.

This distinction was confirmed in White v. Wear (2022) 76 Cal.App.5th 24, where the Court of Appeal held that “the procurement of an amendment to a trust modifying the dispositive provisions constituted financial elder abuse against the trustmaker.” The court concluded that changing an elder’s estate plan through undue influence is not just a basis for contesting the trust — it is a separate and independent act of financial abuse.

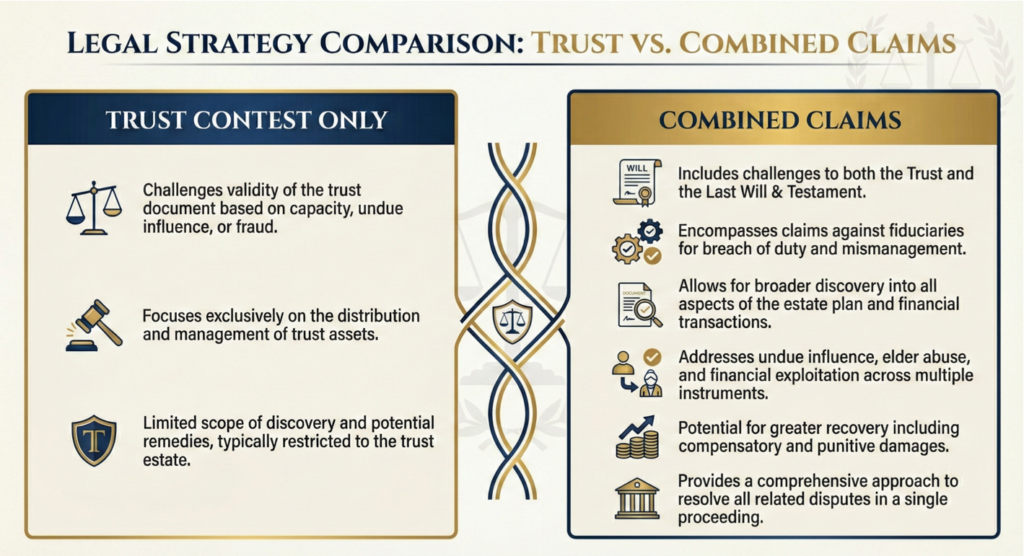

What a Trust Contest Is — and What It Cannot Do Alone

A trust contest is a legal proceeding in which a beneficiary challenges the validity of a trust or a trust amendment. Common grounds for contesting a trust in California include lack of testamentary capacity (the settlor did not understand what they were signing), undue influence (someone overcame the settlor’s free will), fraud (the settlor was deceived about what the document said), and improper execution (the document was not signed or witnessed correctly).

If you win a trust contest, the court invalidates the challenged trust or amendment. The estate reverts to the prior valid version of the trust or, if no valid trust exists, to intestacy under California law. That is a significant result, but it comes with important limitations.

A successful trust contest, standing alone, typically does not entitle the winner to recover attorney’s fees from the losing party. It does not impose financial penalties on the person who procured the fraudulent amendment. And it does not provide a mechanism for emergency court orders to freeze assets or prevent further manipulation while litigation is pending.

This is where the financial elder abuse claim changes everything.

Why Filing Both Claims Together Creates Stronger Litigation Leverage

When a trust contest and a financial elder abuse claim are filed concurrently, the combination unlocks remedies and procedural advantages that neither claim provides alone. Based on published California case law and statutory authority, here is what the combined approach offers:

1. Mandatory Attorney’s Fees

Under Welfare & Institutions Code §15657.5, when a defendant is found liable for financial abuse as defined in §15610.30, the court “shall award to the plaintiff reasonable attorney’s fees and costs.” This is a mandatory fee-shifting provision — the word “shall” leaves no discretion. In a trust contest alone, each side typically bears its own fees. Adding the elder abuse claim converts a self-funded litigation into one where the wrongdoer pays the winner’s legal costs.

2. Probate Code §859 Double Damages

Probate Code §859 imposes a penalty of twice the value of the property recovered when someone has taken trust or estate property “through the commission of elder or dependent adult financial abuse.” This means that if a caregiver or family member used undue influence to transfer $500,000 in trust assets to themselves, the court can order the return of those assets plus an additional penalty of $1 million under the Estate of Ashlock (2020) 45 Cal.App.5th 1066 interpretation. A trust contest alone does not trigger Probate Code §859 double damages — the elder abuse finding is the key that unlocks it.

3. Elder Abuse Restraining Orders

Under Welfare & Institutions Code §15657.03, a court can issue an elder abuse restraining order (EARO) that prevents the abuser from contacting the elder, coming within a specified distance, or — critically — making or facilitating any further changes to the elder’s estate plan. In White v. Wear, the Riverside County Superior Court issued an EARO restraining the stepdaughter for three years from financially abusing 94-year-old Thomas Tedesco, contacting him directly or indirectly, and facilitating any change to his trust. The Court of Appeal affirmed. This type of emergency protective order is available only through an elder abuse claim, not through a trust contest.

4. Presumptions That Shift the Burden of Proof

Under Probate Code §21380, certain transfers are presumed to be the product of fraud or undue influence. These include transfers to the person who drafted the instrument, a person who transcribed it while in a fiduciary relationship with the transferor, and a care custodian of a dependent adult. When the presumption applies, the burden shifts to the beneficiary of the suspicious transfer to prove by clear and convincing evidence that the transfer was not the product of fraud or undue influence. If the transfer was made to the person who actually drafted the document, the presumption is conclusive — meaning it cannot be rebutted at all. Filing a financial elder abuse claim alongside a trust contest allows the litigation team to invoke §21380 presumptions strategically, forcing the wrongdoer to defend their conduct rather than putting the family on the offensive.

5. Jury Trial Right for Elder Abuse Claims

Trust contests are heard by a probate judge in a bench trial. Financial elder abuse claims, however, may be filed in civil court and can carry a right to a jury trial. Some litigation attorneys use this strategically — the threat of presenting an elder exploitation case to a sympathetic jury creates significant settlement pressure that a bench trial in probate court does not.

The Case That Shows How This Works: White v. Wear

The facts of White v. Wear (2022) 76 Cal.App.5th 24 illustrate exactly how financial elder abuse and trust contest claims work together in practice.

Thomas Tedesco, born in 1926, built his wealth through the sale of a family business and the purchase of commercial properties. In 1988, he and his wife Wanda created a trust benefiting their three biological daughters. Wanda died in 2002. Thomas later married Gloria, who had two daughters from a prior relationship, including Debra Wear.

By 2013, Thomas suffered significant cognitive impairment. Gloria began blocking Thomas’s biological daughters from contacting their father and removed their photographs from the house. Gloria and Debra engaged multiple attorneys to facilitate changes to Thomas’s 30-year estate plan, seeking to disinherit his biological children in favor of Gloria and her daughters.

In 2015, Laura White — one of Thomas’s biological daughters and a cotrustee of his trust — petitioned for a conservatorship of Thomas’s estate. Despite the conservatorship, Debra continued facilitating efforts to change the estate plan. In January 2020, a purported trust amendment was signed — without notice to the conservator, the probate court, or the trustees — disinheriting Thomas’s biological children and grandchildren entirely.

Laura filed for an elder abuse restraining order. The Riverside County Superior Court issued the EARO, restraining Debra for three years from financially abusing Thomas, contacting him, facilitating any estate plan changes, and coming within 100 yards of him. The Court of Appeal affirmed, finding that the procurement of a trust amendment through undue influence constituted financial elder abuse sufficient to warrant the restraining order.

The case demonstrates the dual-claim strategy in action: the elder abuse claim provided the emergency restraining order that stopped further manipulation, while the underlying trust contest challenged the validity of the amendments themselves.

How The Legacy Lawyers Pursue Combined Elder Abuse and Trust Contest Claims

The Legacy Lawyers’ approach to cases involving both financial elder abuse and trust contests follows a multi-phase litigation strategy developed through handling hundreds of trust litigation cases across Los Angeles, Orange County, and Southern California since their founding.

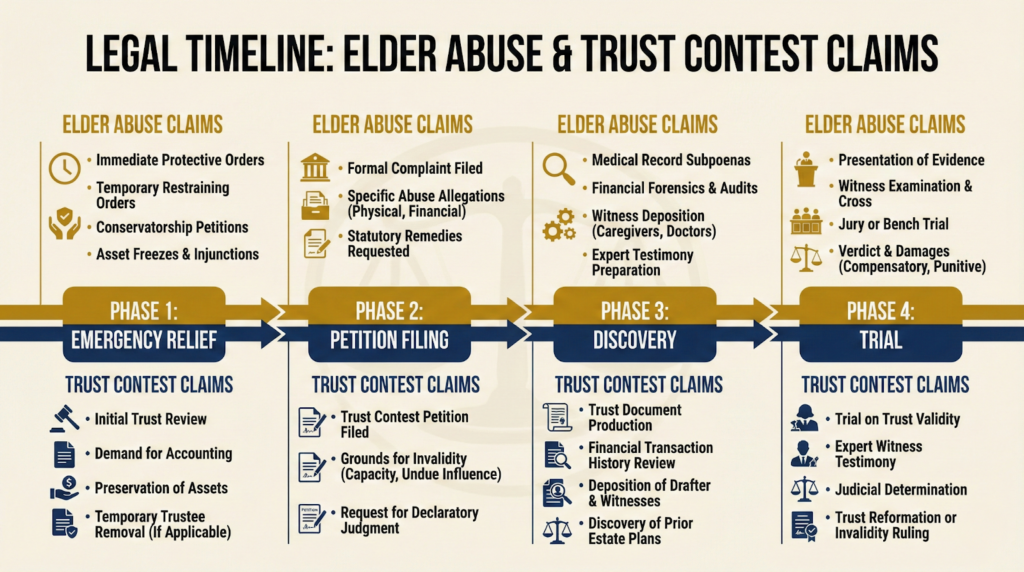

Phase 1: Emergency Protective Measures (Days 1–14)

The first priority is stopping ongoing harm. If the elder is still alive, this may involve filing for an elder abuse restraining order under §15657.03 to prevent further contact, isolation, or estate plan manipulation. If assets are at risk, the team files ex parte applications for temporary restraining orders freezing trust accounts and preventing property transfers. The Legacy Lawyers’ emergency response capability enables filing at Stanley Mosk Courthouse or the applicable Superior Court within hours when circumstances demand it.

Phase 2: Concurrent Petition Filing (Days 14–30)

The litigation team files both the trust contest petition and the financial elder abuse claim, either as a combined proceeding in probate court or as parallel filings depending on strategic considerations. The §850 petition seeks recovery of misappropriated assets. The trust contest challenges the validity of any amendments procured through undue influence. The elder abuse claim invokes §15610.30 and triggers the §859 double damages provision and the §15657.5 mandatory attorney’s fee award.

Phase 3: Discovery and Forensic Investigation (Months 2–8)

Discovery in combined cases is more extensive than in a standalone trust contest. The Legacy Lawyers’ network of forensic accountants traces financial transactions and identifies hidden asset transfers. Private investigators uncover relationships between the alleged abuser and third parties — including attorneys who may have drafted the suspicious documents, which triggers the conclusive presumption under §21380(c). Depositions target both the alleged abuser and any care custodians, attorneys, or financial advisors involved in the estate plan changes. Medical records are subpoenaed to establish the elder’s cognitive state at the time amendments were executed.

Phase 4: Settlement or Trial (Months 8–18)

Combined elder abuse and trust contest cases carry enormous settlement pressure because the wrongdoer faces not just invalidation of the trust amendment, but also double damages under §859, mandatory attorney’s fees under §15657.5, and the potential for a jury trial on the elder abuse claims. The Legacy Lawyers reports that approximately 85% of their trust litigation cases resolve before trial. When trial is necessary, probate matters typically last three to five days, though combined cases with civil elder abuse components may take longer.

Critical Deadlines You Cannot Miss

When elder abuse and trust contests overlap, multiple deadlines run simultaneously. Missing any one of them can permanently eliminate a claim:

- 120 days from receiving a §16061.7 trustee notification to file a trust contest. If this deadline passes without filing, the trust is presumed valid and can never be challenged. The 2024 Court of Appeal decision in Key v. Tyler reinforced that no-contest clauses carry severe consequences, and beneficiaries who litigate risk total disinheritance.

- Three years for financial elder abuse claims based on fraud under Code of Civil Procedure §338(d). However, the discovery rule may extend this if the abuse was concealed.

- Four years for breach of fiduciary duty claims that may accompany the elder abuse and trust contest allegations.

- Immediate action is required for elder abuse restraining orders. EAROs can be filed on an emergency ex parte basis — the court may issue a temporary order the same day, with a hearing on permanent orders scheduled 21 to 25 days later.

If you suspect that a caregiver, family member, or fiduciary has used undue influence to change an elder’s trust, the single most important step is acting before the 120-day trust contest window closes. Once that deadline passes, the trust amendment becomes permanent regardless of how it was procured. Watch for warning signs that a trustee is acting wrongly — they often signal the same conduct that supports an elder abuse claim.

Conclusion

When the Court of Appeal in White v. Wear upheld an elder abuse restraining order against a stepdaughter who helped procure a trust amendment disinheriting a 94-year-old man’s biological children, it confirmed what experienced trust litigation attorneys already knew: financial elder abuse and trust contests are not separate legal problems. They are two sides of the same case, and filing them together creates a litigation framework that is far more powerful than either claim alone.

The combined approach unlocks mandatory attorney’s fees under §15657.5, Probate Code §859 double damages, emergency restraining orders, statutory presumptions of undue influence, and the potential for a jury trial. For families dealing with a trust that was changed through exploitation or manipulation of an elderly parent, the strategic question is not whether to file both claims — it is how quickly you can get them filed before critical deadlines expire.

Call The Legacy Lawyers at (800) 840-1998 to schedule a free consultation. Our trust litigation team will evaluate whether your case involves both financial elder abuse and trust contest grounds, and outline the specific steps to protect your family’s inheritance.

FAQ SECTION

Can I file a financial elder abuse claim and contest a trust at the same time in California?

Yes. These are separate legal claims that can be filed concurrently in probate court or as parallel proceedings. Filing both unlocks remedies — including mandatory attorney’s fees and double damages — that neither claim provides alone.

What is financial elder abuse under California law?

Under Welfare & Institutions Code §15610.30, it occurs when someone takes, hides, or retains an elder’s property for wrongful use, with intent to defraud, or through undue influence. An “elder” is any California resident aged 65 or older.

Does changing an elder’s trust through undue influence count as financial elder abuse?

Yes. In White v. Wear (2022) 76 Cal.App.5th 24, the Court of Appeal held that procuring a trust amendment through undue influence constitutes financial elder abuse because it deprives the elder of their property right to dispose of assets as they intended.

What is the deadline to contest a trust in California?

You have 120 days from receiving a trustee notification under Probate Code §16061.7 to file a trust contest. Missing this deadline permanently bars you from challenging the trust’s validity.

Can I get my attorney’s fees paid by the other side in an elder abuse case?

Yes. Under Welfare & Institutions Code §15657.5, when a defendant is found liable for financial elder abuse, the court must award reasonable attorney’s fees and costs to the plaintiff. This is mandatory, not discretionary.

DISCLAIMER

This article references publicly available information including California Welfare & Institutions Code sections 15610.30, 15610.70, and 15657.5; California Probate Code sections 859, 21380, and 16061.7; and published Court of Appeal decisions including White v. Wear (2022) 76 Cal.App.5th 24, Bounds v. Superior Court (2014) 229 Cal.App.4th 468, Estate of Ashlock (2020) 45 Cal.App.5th 1066, and Key v. Tyler (2024), as well as case summaries published by the California Lawyers Association, Buffington Law Firm, and the Trust on Trial blog by Downey Brand LLP, dated 2014–2026. All metrics and quotes are from documented sources. Results described are specific to the cases cited and may vary based on jurisdiction, facts, and circumstances. For current information about trust litigation services, consult The Legacy Lawyers directly at thelegacylawyers.com.