In Estate of Ashlock (2020), the California Fifth District Court of Appeal upheld a $10 million penalty against a woman who misappropriated roughly $5 million in real property from a decedent’s estate. The court ordered her to return every parcel and pay twice their combined value on top of that. This is the power of California Probate Code §859 — and it exists specifically to punish and deter people who steal from trusts, estates, elders, and other vulnerable parties. If someone has wrongfully taken, concealed, or disposed of assets that belong to your family’s trust or estate, §859 is the most potent litigation weapon available in California probate court. Here is exactly how it works, what it takes to win, and why acting quickly can double — or triple — your recovery.

What Probate Code §859 Actually Says — and Why It Matters for Trust Litigation

California Probate Code §859 is a penalty statute. It states that if a court finds a person “has in bad faith wrongfully taken, concealed, or disposed of property belonging to a conservatee, a minor, an elder, a dependent adult, a trust, or the estate of a decedent,” that person “shall be liable for twice the value of the property recovered.” The court may also award reasonable attorney’s fees and costs at its discretion.

This is not a traditional damages award. As the Fifth District Court of Appeal explained in Estate of Ashlock (2020) 45 Cal.App.5th 1066, the statute “does not impose punitive damages, but it is designed to punish and deter specific misconduct.” The penalty is mandatory once bad faith is proven — the word “shall” leaves no room for judicial discretion on whether to impose it.

The statute works hand-in-hand with two companion provisions. Probate Code §850 allows a beneficiary to petition the court to recover property belonging to a trust or estate. Section 856 empowers the court to order the return of that property. Section 859 then adds the financial penalty on top of the recovery.

There is a critical nuance that expands §859’s reach: the statute also applies when property was taken “by the use of undue influence in bad faith or through the commission of elder or dependent adult financial abuse” as defined under Welfare & Institutions Code §15610.30. This means financial elder abuse claims and trust litigation claims can trigger §859 at the same time, creating powerful leverage for beneficiaries. If you recognize any warning signs of trustee misconduct in your own situation, this intersection of claims is exactly what experienced trust litigation attorneys evaluate first.

How Estate of Ashlock Defined the Real Power of §859

The landmark case that reshaped modern §859 litigation began after Lonnie Ashlock died in 2013 in Stanislaus County. His son Gabriel alleged that Stacey Carlson — the decedent’s girlfriend and real estate broker — had drafted trust documents naming herself as sole beneficiary, signed them on Mr. Ashlock’s behalf, and funneled 18 parcels of real property into sham business partnerships she controlled.

Gabriel filed a §850 petition. What followed was a 53-day bench trial conducted over approximately 18 months between November 2014 and February 2016 — one of the longest probate trials in recent California history. The court found Stacey liable for bad faith misappropriation on all counts.

The Penalty Calculation That Changed California Trust Litigation

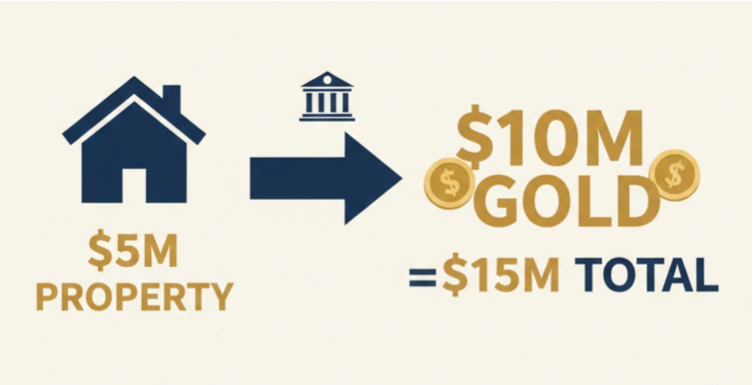

The trial court ordered two separate remedies. First, the return of all 18 parcels under §856. Second, a monetary penalty of approximately $10 million under §859, representing twice the value of the recovered real property, which was collectively appraised at roughly $5 million.

Stacey appealed, arguing that awarding both the property and twice its value effectively amounted to “triple damages.” The Fifth District disagreed. It held that the obligation to return property under §856 is entirely separate from the penalty under §859. The California Lawyers Association summarized the ruling: “a person who misappropriates estate property in bad faith must return the property, plus pay twice the property’s value as a separate penalty.”

“Section 859 does not impose punitive damages, but it is designed to punish and deter specific misconduct. There is nothing punitive about requiring a thief to return stolen property to its rightful owner.” — Estate of Ashlock (2020) 45 Cal.App.5th 1066, 1076

The Appellate Split: What “Double Damages” Actually Means in Your Case

California’s appellate districts are currently divided on how to calculate §859 penalties. Which interpretation applies to your case can mean the difference between recovering double or triple the value of stolen assets.

| INTERPRETATION | CALCULATION | EXAMPLE ($500K TAKEN) | CASE |

| Fifth District | Return property + twice value as separate penalty | $500K + $1M = $1.5M | Estate of Ashlock (2020) 45 Cal.App.5th 1066 |

| Second District | Return property + twice value (agrees with Ashlock) | $500K + $1M = $1.5M | Estate of Kraus (2010) 184 Cal.App.4th 103 |

| Fourth District | “Twice the value” includes the return — caps at double | $500K + $500K = $1M | Conservatorship of Ribal (2019) 31 Cal.App.5th 519 |

The Ashlock court expressly rejected the Ribal interpretation, calling it a deviation “from the plain language of section 859.” As of February 2026, the California Supreme Court has not resolved this split. The applicable interpretation may depend on which appellate district covers your Superior Court — a critical strategic factor that experienced trust litigation attorneys assess at the start of every §859 case.

Under the Ashlock and Kraus interpretation — now controlling in both the Fifth and Second Districts — a beneficiary can potentially recover three times the value of stolen property: the property itself, plus a penalty equal to twice its value. For a $1 million misappropriation, that means up to $3 million in total recovery.

Proving “Bad Faith”: The Legal Standard That Triggers Double Damages

The §859 penalty is not automatic. The statute requires proof that the wrongdoer acted in “bad faith.” This evidentiary burden is where many cases succeed or fail, and it is the reason forensic evidence and experienced litigation counsel are essential.

What Qualifies as Bad Faith

California courts have identified several categories of conduct that satisfy the bad faith standard:

- Forging trust or estate documents — as in Estate of Ashlock, where the court found the defendant drafted and signed trust documents on the decedent’s behalf without authorization

- Transferring assets to personal accounts — in Estate of Kraus (2010) 184 Cal.App.4th 103, a brother used an invalid power of attorney to withdraw $197,402 from his dying sister’s bank accounts the day before she died

- Concealing estate property from beneficiaries — actively hiding assets that rightfully belong to the trust or estate

- Self-dealing by a trustee — using trust funds for personal benefit, paying oneself excessive fees, or making unauthorized loans to associates

- Exercising undue influence over an elder — as defined under Welfare & Institutions Code §15610.70, where excessive persuasion overcomes a vulnerable person’s free will

What Does Not Qualify

Negligent mishandling alone does not rise to the level of bad faith. A trustee who makes poor investment decisions or fails to diversify assets may be liable for breach of fiduciary duty, but that does not automatically trigger §859. The Keading v. Keading (2021) 60 Cal.App.5th 1115 decision raised the additional question of whether bad faith must be proven as a separate element even in financial elder abuse cases — a question that remains open as of 2026.

Understanding what constitutes bad faith versus ordinary negligence is one of the most consequential evaluations in trust litigation. It determines whether your recovery is limited to the return of stolen assets, or whether the court imposes a penalty that doubles or triples the total.

The Litigation Process: How The Legacy Lawyers Pursue §859 Claims

Filing a successful §859 claim requires a structured litigation approach that moves fast to preserve evidence and protect trust assets from further dissipation. Based on The Legacy Lawyers’ documented methodology — refined through 25 years of practice and hundreds of trust litigation cases in Los Angeles, Orange County, and throughout Southern California — the process follows a specific sequence.

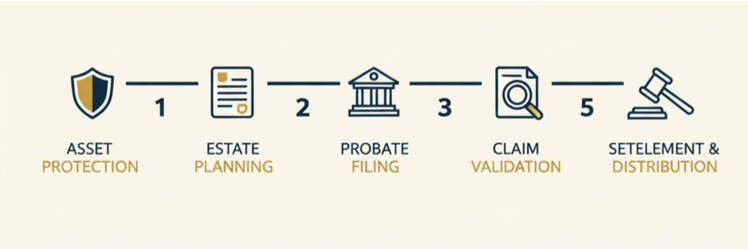

Step 1: Emergency Evidence Preservation (24–72 Hours)

The first priority is securing evidence before it can be destroyed. This means backing up all trust documents, downloading banking records, photographing valuable personal property, and documenting any statements made by the trustee. The Legacy Lawyers’ intake team completes a preliminary document review within 72 hours to determine whether sufficient grounds exist for a §859 claim.

Step 2: Formal Demand and §850 Petition Filing

Within seven days, a formal written demand is sent requesting return of all misappropriated property, citing Probate Code §16061. Simultaneously, the litigation team prepares and files a §850 petition — the procedural vehicle for recovering trust or estate property through the probate court. The petition must specifically describe the §859 relief being sought to provide adequate notice.

Step 3: Emergency Court Relief

When assets are at risk of further dissipation, The Legacy Lawyers routinely seek emergency court orders: temporary restraining orders freezing trust assets, preliminary injunctions blocking specific transactions, and appointment of temporary trustees. These protective measures stop the wrongdoer from spending or hiding assets while litigation proceeds.

Step 4: Discovery and Forensic Investigation

Discovery involves subpoenas to banks and financial institutions, depositions of the wrongdoer and relevant witnesses, and forensic accountants tracing misappropriated funds. The Legacy Lawyers’ network includes California-licensed forensic accountants and private investigators who specialize in uncovering hidden financial relationships and following asset transfers across accounts.

Step 5: Settlement or Trial

Approximately 85% of The Legacy Lawyers’ trustee removal and misappropriation cases settle before trial. Settlements typically include trustee resignation, full accounting, damage payments, and attorney fee reimbursement. When cases go to trial, they typically last three to five days, with courts issuing decisions within approximately 30 days.

Critical Deadlines and Statutes of Limitations

There is no single statute of limitations for §859 claims. Because §850 is a procedural mechanism rather than a standalone cause of action, courts apply the limitations period of the underlying claim:

- Three years for claims based on fraud (Code of Civil Procedure §338(d))

- Four years for claims based on breach of fiduciary duty

- 120 days for trust contests after receiving a trustee notification under Probate Code §16061.7

Timing directly affects recovery amounts. According to data compiled from Los Angeles County Superior Court filings and referenced by The Legacy Lawyers, trust accounting petitions filed within one year of suspected fraud resulted in average recoveries of $485,000, while cases delayed beyond three years averaged only $210,000. Acting quickly is not just a legal requirement — it is the single biggest factor in maximizing your recovery.

If you are a beneficiary and you suspect something is wrong, one immediate step can protect your rights: send a certified letter to the trustee requesting a complete copy of the trust document and all financial records. This begins the evidence trail, may extend certain contest deadlines by 60 days, and establishes the documentation your litigation attorney will need to build a §859 case. For a complete overview of what the law guarantees you, review your beneficiary rights under the California Probate Code.

Conclusion

When Stacey Carlson misappropriated $5 million in real property from Lonnie Ashlock’s estate, the court did not simply order her to return it. Under Probate Code §859, she was ordered to return all 18 parcels and pay an additional $10 million penalty — a total exposure exceeding $15 million. That outcome, affirmed by the Fifth District Court of Appeal and aligned with the Second District’s ruling in Estate of Kraus, established that §859 is the most powerful recovery tool available in California trust and estate litigation.

If someone has wrongfully taken, concealed, or disposed of property belonging to your family’s trust or estate, §859 gives you the legal basis to recover far more than what was stolen. The critical variable is time. The sooner evidence is preserved and a §850 petition is filed, the stronger your claim and the higher your potential recovery.

Call The Legacy Lawyers at (800) 840-1998 to schedule a free consultation. Our team of trust litigation attorneys will review your case, identify whether §859 applies, and outline the specific steps to protect your inheritance.

FAQ SECTION

What is Probate Code §859 in California?

It is a penalty statute that requires anyone who wrongfully takes trust or estate property in bad faith to pay twice the value of the recovered property. The court may also award attorney’s fees. The penalty is in addition to the return of the stolen property itself.

How much can I recover under §859?

Under the Estate of Ashlock (2020) interpretation followed by the Fifth and Second Districts, you can recover the property plus twice its value — effectively tripling your recovery. For $500,000 in stolen assets, that could mean up to $1.5 million total.

Do I need to prove the trustee acted intentionally?

Yes. Section 859 requires proof of “bad faith,” which means intentional misconduct — not just negligent mismanagement. Evidence of forgery, concealment, self-dealing, or undue influence typically satisfies this standard.

What is the statute of limitations for a §859 claim?

There is no single deadline. The limitations period depends on the underlying claim: three years for fraud, four years for breach of fiduciary duty, and 120 days for trust contests after receiving a §16061.7 notification.

Can I pursue §859 double damages and financial elder abuse claims at the same time?

Yes. Section 859 explicitly covers property taken through “the commission of elder or dependent adult financial abuse” under Welfare & Institutions Code §15610.30. Filing both claims simultaneously creates stronger litigation leverage and may support additional remedies.

This article references publicly available information including official California Probate Code sections, published Court of Appeal decisions (Estate of Ashlock (2020) 45 Cal.App.5th 1066, Estate of Kraus (2010) 184 Cal.App.4th 103, Conservatorship of Ribal (2019) 31 Cal.App.5th 519, Keading v. Keading (2021) 60 Cal.App.5th 1115), and case summaries published by the California Lawyers Association, dated 2010–2026. All metrics and quotes are from documented sources. Results described are specific to the cases cited and may vary based on jurisdiction, facts, and circumstances. For current information about trust litigation services, consult The Legacy Lawyers directly at thelegacylawyers.com.